Negative space

9 min read

Pixar is a really interesting company. They started doing research on computers and images, turned into a technology company and then moved to their aspiration of creating animation feature films. The book Creativity, Inc. [1] tells their story starting from its inception by George Lucas, then the acquisition by Steve Jobs until their association with Disney. The author, Ed Catmull, former president of Pixar Animation, explains that just after they released Toy Story they created a Pixar University, initially meant to deliver training on their proprietary software but soon after they included other topics.

They introduced a course to teach everybody in the company to draw, even though they already had people who could draw beautifully. They did it because they thought there is something underlying the process of drawing that everybody needed to understand. They taught workshops based on the 1979 book by Betty Edwards Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain [2] to improve observation skills. Edwards’ book uses the concepts of right and left brain, being the left verbal and analytical and the right more visual and perceptual. Part of the process of learning to draw is learning to see, and in order to achieve this, you need to shut down your left side of the brain.

For example, when you try to draw a chair, you know it has four legs and you’ll try to represent that mental model from your head, regardless of whether you see the legs or not. People who draw better can set aside their preconceptions. It is important to disconnect from language and logic when we are drawing and focus only on what we are seeing now.

There are different ways to train for this. One is placing the model we are trying to draw upside down so that the student cannot recognise the object and sees just only shapes. The left side of the brain will not step in because it sees no familiar references. The right side of the brain will work only on sizes and relative distances of what is seen.

Another technique is to ask students to draw “all that is not the object”. To draw the contours, the surroundings, the boundaries that define what is not the object to draw: the negative space. In the example, when drawing the negative space of the chair, the student is not going to use their mental model of the chair and the proportions are going to be taken more easily, focusing only on what’s in front of them. There is not going to be any meaning added to what is seen, suspending all previous knowledge, all judgement, and all the impulses that can distort their vision.

As fascinating as it is, this is not about drawing, but about being able to see “what is not there”.

Shaping the organisation

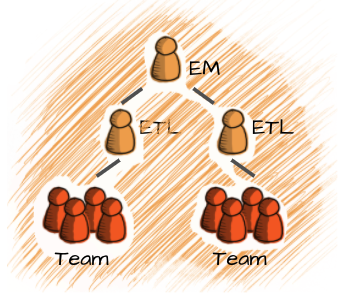

In Team of Teams [3, Ch. 138] the author mentions the acronym MECE (pronounced mee-see), which stands for “mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive”. A MECE breakdown has the intention of dividing a whole into a series of categories that do not overlap but together cover everything. An org chart has the intention of being a MECE structure: nobody assumes there is going to be something left uncovered and there is a lot of effort in clarifying responsibilities that do not overlap.

Even though that is the intention, eventually you will find elements in the organisation that are not covered or that have duplication. From there, you can delineate the negative space of the organisation.

Going back to the org chart, the hierarchy clarifies the assignment of responsibilities, useful when there is arbitrage needed. If something is not clear at the team level, the Team Leader can step in to clarify. When something is not clear between teams, the supervisor of the group of teams can solve the dispute. But when the differences are in something that is not in the defined responsibilities of any team, the negative space, it is hard to tell looking at the org chart who has to help with the problem and the question may be left forgotten until it becomes a serious problem. Who owns it? Who has to coordinate? Should the CEO intervene? That would not make sense.

Mechanical solution

An approach to solve this problem, presented in a different way, suggests eliminating the space in between the teams. The book Team Topologies [4] suggests that the organisation should be structured in a way that the smaller actor is the team (not the individual), teams interact in clearly defined modes (collaboration, as a service or as facilitators) and there are four types of teams: stream-aligned teams (the preferred type), enabling teams, complicated subsystem teams and platform teams.

Authors of this solution obviate the structures above the teams, the management, and external companies. Their promise is that any dependency between multiple teams is solved through a platform.

I agree they provide a very valid thinking tool and a good vocabulary to talk about teams and their relationships. Even I accept that their solution could improve certain organisations, but I don’t think it’s applicable in all environments.

It is complex

Maybe we are asking the wrong question. We are trying to find the pieces that form an organisation and put them together to build the whole puzzle. We are thinking about the organisation as if it was a machine and we need to find the solution. Where is the missing piece?

General McChrystal, trying to improve adaptability over efficiency, found that anti-MECE organisations worked better. The redundancy of responsibilities creates inefficiencies that allow adaptability and efficacy [3, p. 139]. “Great teams are less like ‘awesome machines’ than ‘awesome organisms’.”

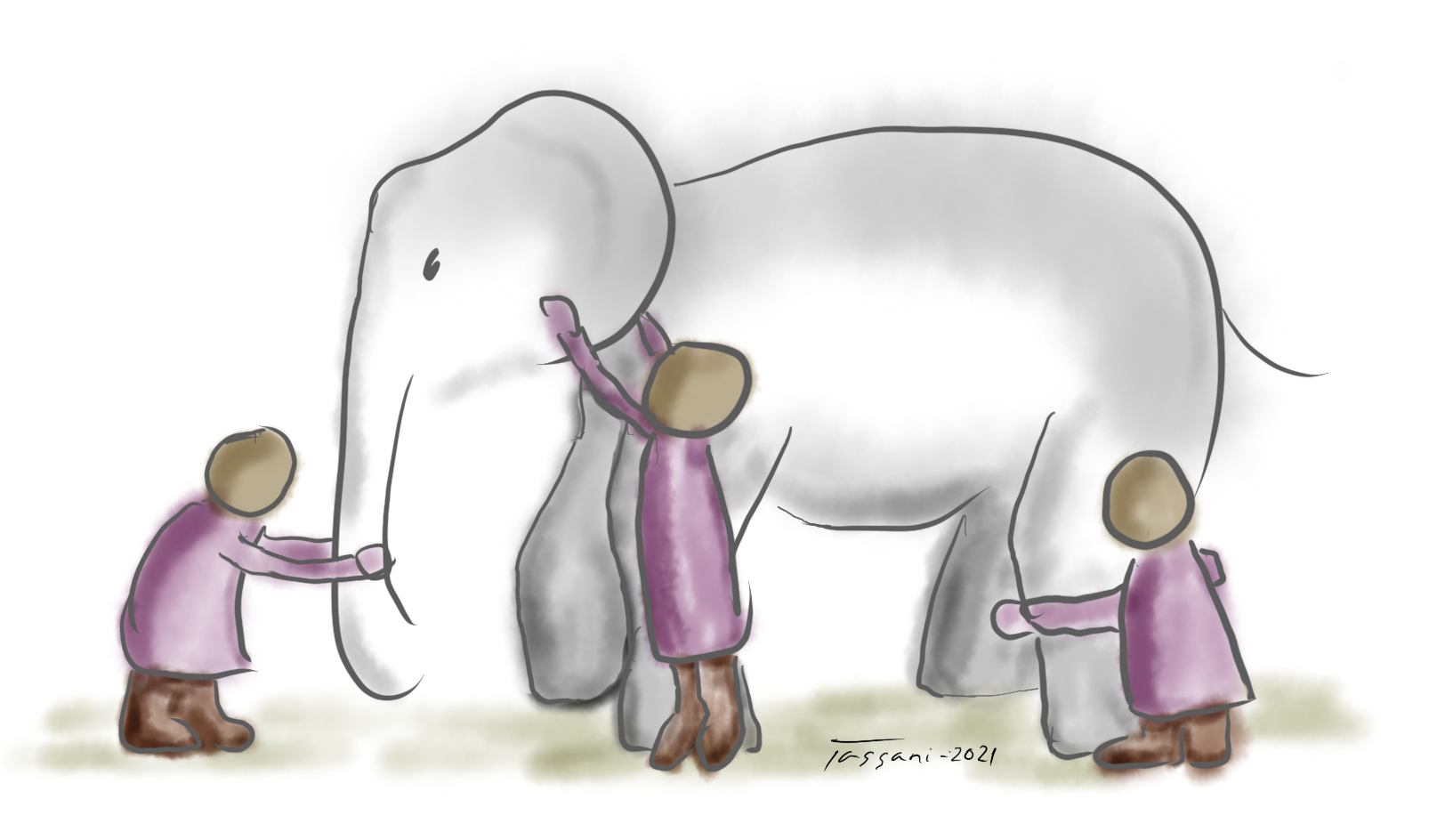

An old parable goes like this: Three blind men, who have never come across an elephant, try to learn what it is by touching it. One of them says “it’s like a tree”, while hugging its leg. Another one says “I have the real facts and it is wide and broad, like a rug”, touching the ear. The third man, reaching out the trunk says, “you all are wrong, it is like a snake”. All of them were wrong and all of them were partially right [5].

A system is more than the sum of its parts [6, p. 11]. I tend to use the language of machines and factories when talking about teams, input and output. It’s easy to understand but I am perpetuating the image of the machine.

While we find a better language (living organisms? gardens?[7]) we can talk about the negative space to think on how to improve the way we work.

Toni Tassani — 11 April 2022

This article was originally published on 1 March 2021 on the company intranet.