Language and thinking

9 min read

The Inuit live in the Arctic regions of Alaska, Greenland and Canada, always in freezing temperatures, and that’s why they have more than one hundred words to refer to snow. We don’t have as many words in English, so we cannot be as precise as they are when talking about it. Their world has influenced their language and now their language influences how they perceive and think.

As intuitive as this story sounds, it is not true. It comes from a misunderstanding from Benjamin Lee Whorf of how these people construct words but many people consider it to be true [1].

The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, also known as linguistic relativity, suggests that the structure of a language affects the way people think and perceive their world. Named after Edward Sapir and Benjamin Lee Whorf, American anthropologists and linguists, this idea has been criticised and refuted.

For instance, there are languages that don’t have different words for the colours green and blue, named grue languages, but speakers of these languages have no problem distinguishing the two colours [2]. The same thing happens to the Zuñi people in New Mexico, that don’t have different words for orange and yellow [3]. The constraints in their language do not affect their perception.

What’s in a name? That which we call a rose

By any other name would smell as sweet.

— Juliet in Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet

Influencing cognition

The linguist Lera Boroditsky provided very interesting examples about how language influences our thinking in her 2017 TED Talk, How language shapes the way we think [4].

There are languages that cannot express quantities, they don’t have numbers so they cannot use arithmetic as we know it.

She has studied an Aboriginal community in Pormpuraaw, Australia. They don’t have the words for “left” and “right” but they describe the location of objects by compass directions: north, south, east and west. They are used to knowing at every moment where the north is. They will refer to their “east foot” and they will not get confused talking about “your right, not my right”. They are not biologically equipped differently, but they have included this skill in their language and culture. Their usual greeting, instead of “hello”, is an exchange like “where are you going?”, “south-southeast”.

Some languages like Chinese don’t have grammatical forms to talk about present and future. Keith Chen, a professor of economics at UCLA, has found that Chinese people are more likely to save money than people who use languages that can express the future. It seems that if you can’t depict in your language your future-self it’s less likely you think about them as a different person, and you will make more considerate decisions.

“Language is very powerful. Language does not just describe reality. Language creates the reality it describes.”

― Desmond Tutu

The way our language uses to report events also influences how we remember them. Imagine a case where a vase was accidentally broken. It is natural for English speakers to report who broke it as in, “Veronica broke the vase”. Saying “the vase has been broken” would be perceived as trying to conceal the author. However, in Spanish the natural thing to do would be to omit the subject and this affects how we remember the event.

Left to right and right to left

In the film Arrival, Amy Adams plays a linguist who is deciphering an alien language, and by understanding better their language her perception of time changes. That is fiction, but Boroditsky reports other ways perception of time and space is influenced by language. In an experiment [5] she asked people to sort people pictures chronologically. People who are used to languages that are written left to right used that direction. People from Pormpuraaw, mentioned before, first had to determine where they were facing, and then organised the pictures from east to west. And people writing right to left, like in Hebrew, positioned the pictures in that order.

About right to left language. Long ago I saw a picture of a kanban board that seemed to have the columns in the “wrong” order, having done items on the left. I found the cover of the Hebrew version of Agile kids - Who’s the boss of me? with the sticky notes on the right, instead of on the left, so I asked the author, Shirly Ronen-Harel. She said that in Hebrew they write right to left, except numbers, that are left to right. In professional environments, a visualisation board would use left to right like in English because they are used to it, but for kids she suggested right to left to be less confusing. I found it really interesting!

The gender case

There are different ways a language can represent gender. Some languages have natural gender, with the capacity to differentiate living male things, such as boys, fathers, and uncles, from living female things such as girls, mothers, and aunts. In English there is “he” and “she” to make this kind of distinction, but “they” can be used to refer to a singular third person if the gender doesn’t have to be specified.

Other languages have grammatical gender, so that all nouns have an assigned gender, regardless whether they are naturally masculine or feminine. Instead of using an equivalent to the neutral “it” they use the equivalent to “he” or “she” to refer to every noun. Pronouns, adjectives, possessives and so on, also have masculine and feminine declination.

The gender is completely arbitrary and it causes confusion when learning these languages. For instance, “sun” is masculine in Spanish and feminine in German, and “moon” is feminine in Spanish and masculine in German.

To have a second language is to possess a second soul.

— Charlemagne

Does the arbitrary gender influence how the speaker thinks? It turns out that Lera Boroditsky asked subjects to describe certain words and participants chose adjectives that were usually attributed to the grammatical gender of the word. For example, the word “key”, is masculine in German and feminine in Spanish. For German speakers it was “hard”, “heavy” and “useful”, and for Spanish speakers it was “little”, “lovely” and “tiny”. A “bridge”, feminine in German and masculine in Spanish, for German speakers was “beautiful” and “elegant”, and for Spanish speakers was “dangerous” and “strong” [5].

How do these languages handle non-binary people? Do they have to be referred with the binary articles, determinants and adjectives? In English, not having a prevalent grammatical gender, it is easier, but words like “actor” and “actress”, “prince” and “princess” or “waiter” and “waitress” have to be adapted. For other languages, there are some initiatives trying to promote gender neutral language in German, Spanish, Polish and others, even though it is not widely accepted.

The value of diversity

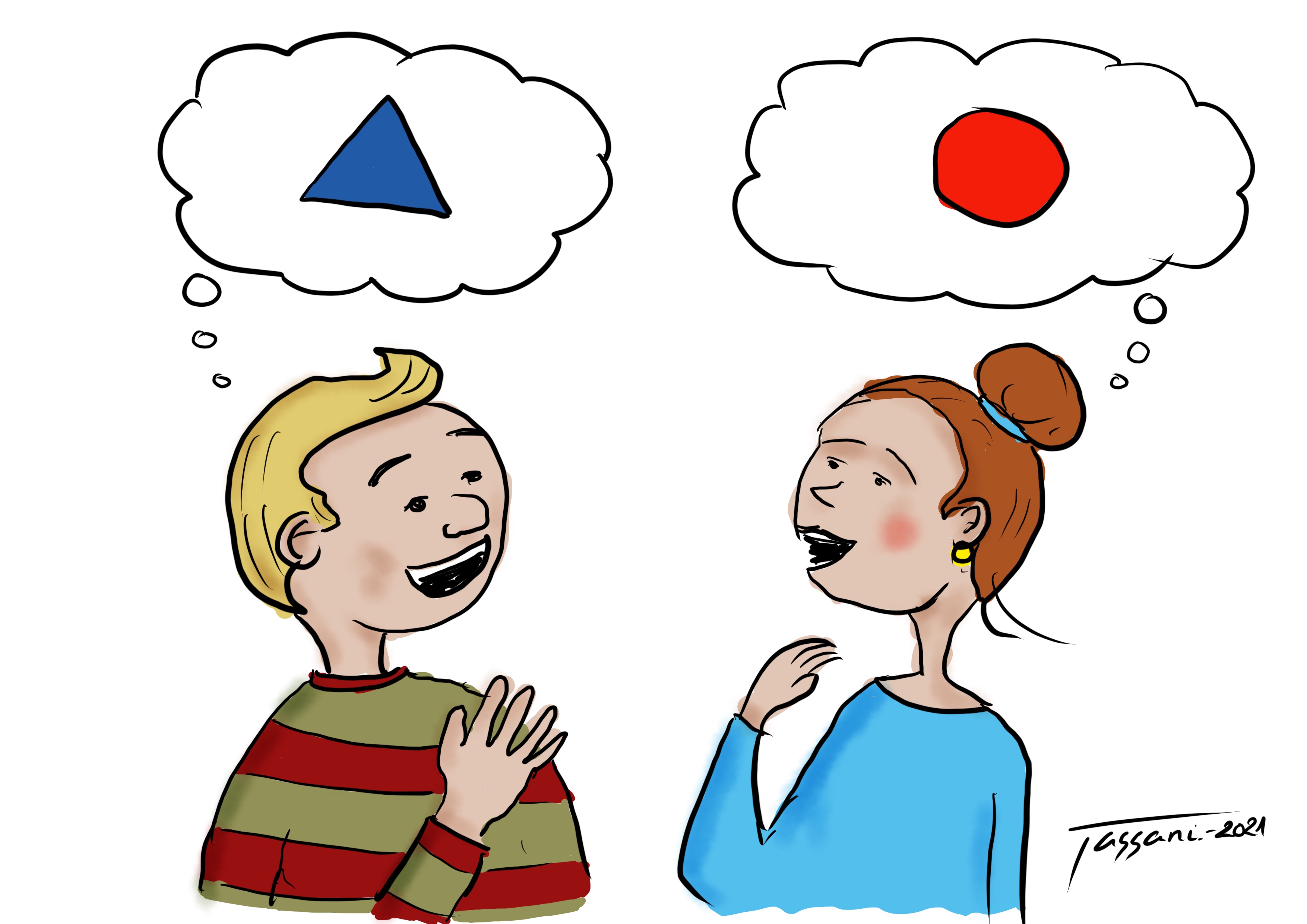

There are more than 7,000 languages in the world. Each language creates a filter for their speakers that, somehow, seems to affect the way they perceive and think. The more ways of thinking we add to solve problems, the more options we’ll have to solve them.

The single biggest problem in communication is the illusion that it has taken place.

— George Bernard Shaw

Toni Tassani — 24 Oct 2022

This article was originally published on 10 May 2021 on the company intranet.